Ella Yolande

But Why Tarnish the Beauty of a Flower (2023)

Single-Channel HD Video

5 mins, 40 secs

Screened 8-30 April 2024

-

-

Relation de Voyage

Ella Yolande: But Why Tarnish the Beauty of a FlowerBut Why Tarnish the Beauty of a Flower uses recorded attempts to virtually access and experience botanical gardens and glasshouses via Googlemaps combined with 3D scans from Kew Gardens, to consider the colonial histories of these sites. The video emerged from an online residency with 11:11 Residency in 2022, looking into botanical histories and the extraction and commodification of plants through the legacies of plant hunters. The botanical sciences that developed in the 17th and 18th century were a project for the ordering, visualising, labelling and categorising of life that feeds into the continued stratification and hierarchies of bodies. There was an established assumption of landscape and plants as passive and inactive matter. Growing from an interest in these sites that impose a surreal and static power over a clean, curated display of ‘nature’ and wondering what ends up in the compost, the piece touches on the mapping, movement and categorisation of plants and their values. Considering the accompanying tensions between preservation, extraction and adaptability prompts questions of what botanical gardens might function as and what plants might look like in the future.

With thanks to Residency 11:11 for supporting the making of But Why Tarnish the Beauty of a Flower

-

Making the rock into home by Cecelia Graham

In response to But Why Tarnish the Beauty of a Flower by Ella Yolande and the accompanying works I Found Roots Around my Spine and Glasshouse Symbol IRearranged in clean curation

A few days ago I observed someone, mid-conversation and bored, scraping moss off a gravel path with their foot. The moss became unanchored, its tether to the earth dislodged by the edge of a Nike trainer. Later, I googled the conditions for moss to grow on human made surfaces. Rather than finding out the answer for the perfect mossy microclimate, I encountered prevention tips. Sprinkle salt to kill the moss, make a concoction with bleach, power hose, break it up, keep your ground clean, sweep.

The same day, I fell into a Tik Tok vortex of moss decor videos. I watched as people documented their creation of moss bordered mirrors, decorative sculpted moss bowls and art consisting of moss pinned to a canvas. One creator commented that their moss mirror took FOREVER to make. The moss they used was real, plush and dense, undoubtedly pulled from its decades long home. If we’re not scuffing nature with our shoes, we’re capturing it, reducing it to scenery, upholstering our mirrors and decorating our walls.

Land, roots and routes

In Ella Yolande’s video work But why tarnish the beauty of a flower, the artist references Orchid Fever, the obsessive Victorian craze amongst the upper classes to discover and collect orchids from around the world. Explorers were sent to far flung locations to find new orchid species, bringing their wares to unsuitable European gardens via auction houses. The orchids, forcibly relocated to an inhospitable home, often died due to transplant shock - the inability to root in the soil.

In The Orchid Hunters, published in 1939, Norman McDonald writes ‘When a man falls in love with orchids, he’ll do anything to possess the one he wants.’

I think about this in relation to an anecdote told by Robin Wall Kimmerer in the book Gathering Moss. Kimmerer tells a similar story of commodification, as she recounts being invited to be a moss consultant for what she initially believes to be an educational project in Appalachian vegetation restoration. Instead, it transpires to be a landscaping project, decorating the garden of a wealthy man who wishes to give the illusion of antiquity to his golf course backdrop through moss propagation. It’s destined for failure, the moss harshly taken from its own microclimate and super glued onto rocks. To destroy a thing for pride, writes Kimmerer, is a potent act of domination.

Ownership and possession, the thirst for the exotic, tears the orchid or the moss away from generations of flourishing - hasty excitement, forever wounds.

Questioning categories

As Orchid Fever reached its peak, so too did the Victorian era’s obsession with classification within Botany. Kew Gardens, established as a national botanical garden in 1840, became a major influence in not just the categorisation of plants but the practice of categorisation as a whole. There is an order to everything in labelling systems and, under this structure, nature is confined within human-made notions, becoming something passive to take and reshape.

In Ella’s video work, we are guided digitally through botanical gardens, the scale of their presence mediated on screen. These sites are spaces of extraction, as local plants and the knowledge that comes with them is erased and planted in a controlled environment. This isn’t about preservation, it goes back to that thirst that Ella writes about. Plants, categorised and renamed often in Latin, are given the language of the coloniser, erased and dominated.

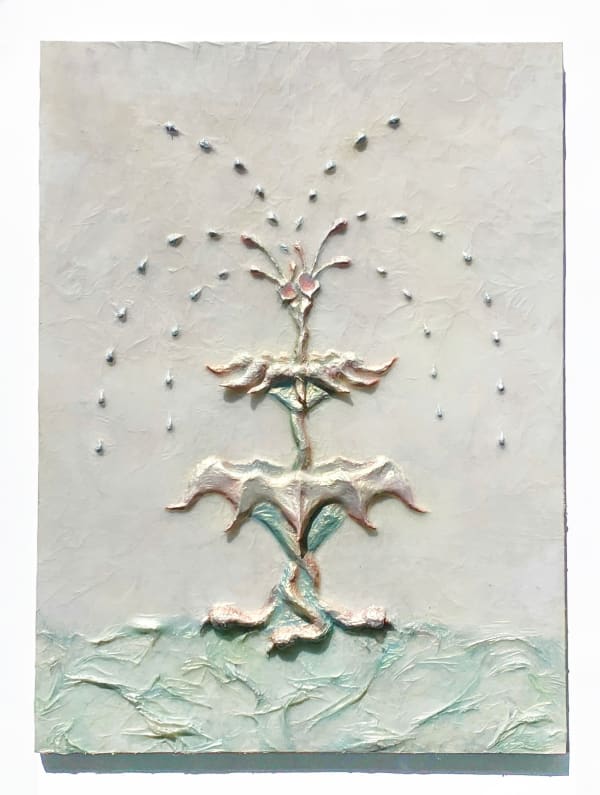

The botanical gardens form the backdrop to 3D scans taken from Kew Gardens, made into hybrid plant species. The plants, adapted and fluctuating, both speak to this colonisation and un-do it. Having extracted the plants from their natural environment, Kew Gardens would then hybridise them as their attentions turned to profit. These new plant species would then be planted as monocultures across the world in new plantations, with other native vegetation torn at the roots and destroyed.

The hybrid plants, created by Ella, are slippery forms, imbued with agency as their tendrils stretch and slowly shape shift. These new plant forms cross over time scapes, holding the past and the future in their organic bodies. Undoing the rigidity of categorisation, the speculative plants of the future are not named by the artist, nor are they clean forms. Instead they are entangled, multiples co-existing at once, their lives ‘our debt to those who are already dead and those not yet born’ (1).

-

Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/continuities, SpaceTime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-Come, Karen Barad. A reference from Ella Yolande’s Digital Residency We Have Never Been Only Human with CCA Derry~Londonderry, 2023.

References

-

Gathering Moss, Robin Wall Kimmerer

-

Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/continuities, SpaceTime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-Come, Karen Barad. A reference from Ella Yolande’s Digital Residency We Have Never Been Only Human with CCA Derry~Londonderry, 2023.

-

Normal McDonald, The Orchid Hunters

-

Ros Gray and Shela Sheikh, The Coloniality of Planting: Legacies of racism and slavery in the practice of Botany in The Architectural Review, 2021

Cecelia Graham is a curator based between Belfast and Mid-Ulster in the North of Ireland

-

-

Ella Yolande

Portrait of Ella Yolande

Portrait of Ella Yolande